Functional Parallel Programming in the wild

by Anzori (Nika) Ghurtchumelia

1. Introduction

🚀 Welcome to a journey where functional programming meets the social media hub for developers - GitHub! 🌐.

If you’ve ever wondered how to turbocharge your software projects with parallelism, you’re in for a treat.

Today, we’re diving into the world of Scala and Cats-Effect fibers by solving a practical problem.

Picture this: GitHub as the bustling city for developers, with repositories as towering skyscrapers and code collaborations. Now, what if I told you there’s a way to navigate this huge metropolis within seconds? Enter functional programming, the superhero caped in composability and scalability 😊.

In the vast landscape of open-source collaboration, aggregating an organization’s contributions can be a challenge. In this blog, we unravel an efficient solution to aggregate contributors concurrently. We will witness how Scala’s support for parallel programming can transform the task of “contributors aggregation” into a “piece of cake”.

Simply put, we’re creating an HTTP server to compile and organize contributors from a specific GitHub organization, like Google or Typelevel. The response will be sorted based on the quantity of each developer’s contributions.

2. Project Structure

We will use Scala 3.3.0, SBT 1.9.4 and a handful of useful libraries to complete our project.

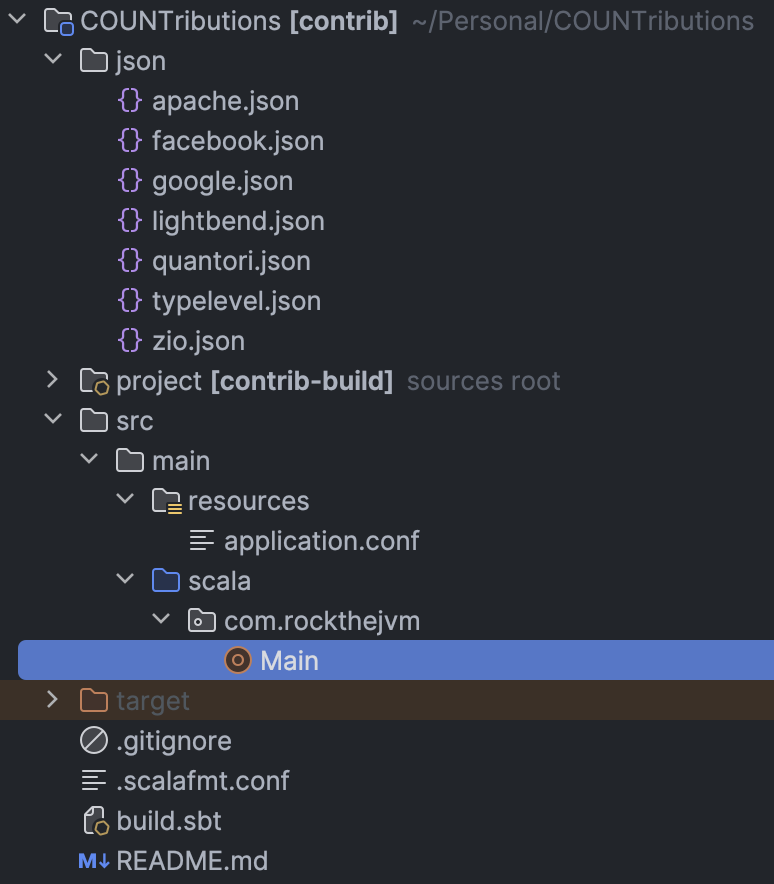

The initial project skeleton looks like the following:

jsonfolder contains the JSON outputs for each organizationsrc/main/scala/com/rockthejvm/Main.scalais a single file 150 LOC solutionsrc/main/resources/application.confdefines the project configuration (in this case only a GitHub token for authorizing GitHub requests).scalafmt.confis used to format the code (UI/UX is important, even for backend devs 😉)build.sbtis responsible for building the project and generatingapp.jarwhich we can run withjavaorscala

Let’s have a look at the libraries listed in build.sbt:

val Http4sVersion = "0.23.23"

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.settings(

organization := "com.rockthejvm",

name := "contrib",

scalaVersion := "3.3.0",

libraryDependencies ++= Seq(

"org.http4s" %% "http4s-ember-server" % Http4sVersion,

"org.http4s" %% "http4s-ember-client" % Http4sVersion,

"org.http4s" %% "http4s-dsl" % Http4sVersion,

"com.typesafe.play" %% "play-json" % "2.10.3",

"com.github.pureconfig" %% "pureconfig-core" % "0.17.4",

"ch.qos.logback" % "logback-classic" % "1.4.12" % Runtime,

),

)

- first three dependencies which start with

org.http4sare concerned with the HTTP server & client and handy dsl for creatingHttpRoutes play-jsonis a JSON library for Scala- last two libraries will be used for managing project configuration and logging respectively

3. Prerequisites

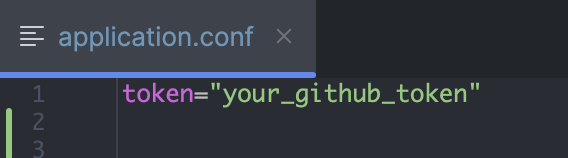

Before doing anything, please generate personal GitHub access token and put it in src/main/resources/application.conf, like this:

It is necessary to use GitHub token because we’ll be using GitHub API for which the requests must be authorized. Also, GitHub token will ensure that GitHub API rate limiter will allow us to issue many requests at once.

Please, have a look at the GitHub docs to do it.

4. Planning

What are we going to do and how exactly? To answer these questions we must investigate existing GitHub API so that we know what kind of data is exposed and how.

Some of the interesting questions can be:

- How can I fetch basic data about an organization?

- How do I find out how many public projects are owned by the organization?

- What is the number of contributors for each project owned by the organization?

- …

5. Quickstart

Let’s just create a Main.scala and run a basic HTTP server with health check endpoint to ensure that everything is fine.

package com.rockthejvm

import cats.effect.{IO, IOApp}

import org.http4s.dsl.io.*

import org.http4s.ember.server.EmberServerBuilder

import org.http4s.HttpRoutes

import org.typelevel.log4cats.Logger

import org.typelevel.log4cats.slf4j.Slf4jLogger

import org.typelevel.log4cats.syntax.LoggerInterpolator

import com.comcast.ip4s.*

object Main extends IOApp.Simple {

given logger: Logger[IO] = Slf4jLogger.getLogger[IO]

override val run: IO[Unit] =

(for {

_ <- info"starting server".toResource

_ <- EmberServerBuilder

.default[IO]

.withHost(host"localhost")

.withPort(port"9000")

.withHttpApp(routes.orNotFound)

.build

} yield ()).useForever

def routes: HttpRoutes[IO] =

HttpRoutes.of[IO] { case GET -> Root =>

Ok("hi :)")

}

}

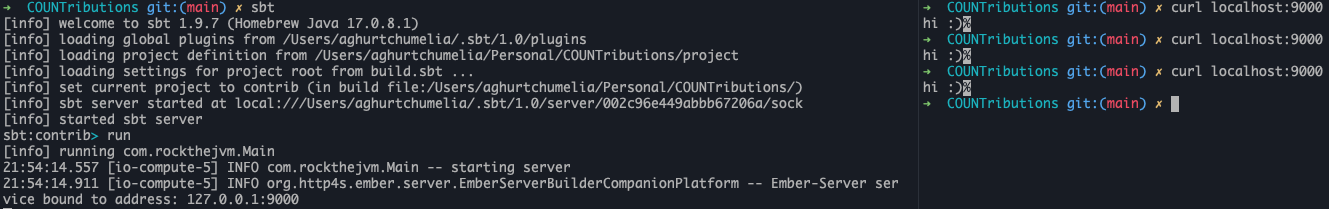

To start the app we need to execute sbt and run commands:

sbtrun

and then test our server by curling it:

curl localhost:9000

To illustrate all that:

Great! Now it’s time to move on to some domain modeling.

6. Domain Modeling

It turns out that GitHub API responses support JSON format, it means that we’ll need to define custom JSON deserializers for our domain models.

Since we’re working on “GitHub Organization Contributors Aggregator” we’d probably need to think in terms of following nouns:

- Organization

- Project

- Contributor

- …

Also, it’s important to keep in mind what is returned by each REST API request so that our deserializers do not fail unexpectedly.

Let’s start by Organization. Organization is a group of developers that develops multiple open source projects, however the only thing we’re interested is the amount of public repositories it owns.

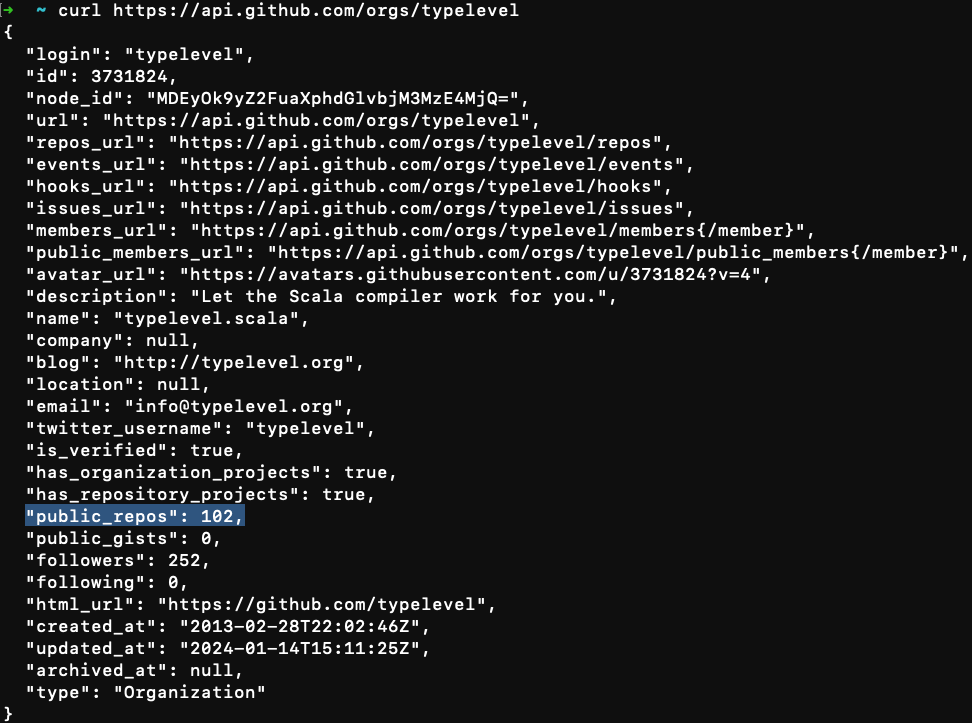

Turns out that if we send a basic request to "https://api.github.com/orgs/$orgName" we will get a JSON response back, in which we could find the amount of public repositories.

For example, let’s pick an organization - typelevel and test it:

Nice, so we have our first interesting domain object - Amount of public repositories, let’s model that, shall we? :)

Since it’s just a number we could use Int or Long but Scala 3 supports opaque types, so it’s better to use that.

Let’s create a domain object in Main.scala and put everything there with the intention of being compact and fitting everything in one picture.

object domain {

opaque type PublicRepos = Int

object PublicRepos {

val Empty: PublicRepos = PublicRepos.apply(0)

def apply(value: Int): PublicRepos = value

}

extension (repos: PublicRepos)

def value: Int = repos

}

We’ve defined an opaque type which essentially is an Int. It has an apply constructor and Empty value. apply defines the method in the companion object. It allows you to create instances of PublicRepos by calling PublicRepos as if it was a function, passing an integer value as an argument, this way we could avoid additional wrapping cost over simple integers.

Empty value can be used in case the key is absent in JSON, or in case it has a negative value. The latter one is less likely to happen, but let’s choose the safer road and insure ourselves with a sensible fallback - 0.

With the value extension method, we can easily retrieve the underlying Int value for PublicRepos.

As for the deserializer for PublicRepos - it will be really simple. We would just want to read "public_repos" key from JSON, so we’d define that in domain object in the following way:

object domain {

import play.api.libs.json.*

import play.api.libs.*

import Reads.{IntReads, StringReads}

/**

* some PublicRepos definitions

* ..

* ..

*/

given ReadsPublicRepos: Reads[PublicRepos] = (__ \ "public_repos").read[Int].map(PublicRepos.apply)

}

Let’s break down step by step what is going on here:

given ReadsPublicRepos: This declares an implicit value namedReadsPublicReposof typeReads[PublicRepos]. In Scala 3,givenkeyword is used to define implicit values.Reads[PublicRepos]: This indicates that the implicit value is an instance of theReadstype class for thePublicRepostype. TheReadstype class is typically used in Play JSON to define how to read JSON values into Scala types.(__ \ "public_repos"): This is a Play JSON combinator that specifies the path to the"public_repos"field in a JSON structure. It is part of the Play JSON DSL and is used to create a reads for the specified field..read[Int]: This part of the code specifies that the value at the path"public_repos"in the JSON structure should be read as an Int. It’s defining how to extract an Int value from the JSON..map(PublicRepos.apply): This maps theIntvalue obtained from reading the"public_repos"field to aPublicReposinstance using thePublicRepos.applymethod. It essentially converts the extracted Int value into aPublicReposinstance.

So, when you have JSON data representing a structure with a "public_repos" field, you can use this given Reads instance (ReadsPublicRepos) to convert that JSON into a PublicRepos instance.

As soon as we have PublicRepos we could also define something like a placeholder for the repository name, maybe - RepoName.

RepoName is as trivial as PublicRepos, however, obviously it’s not a number:

object domain {

import play.api.libs.json.*

import play.api.libs.*

import Reads.{IntReads, StringReads}

/**

* code

* ..

* code

*/

opaque type RepoName = String

object RepoName {

def apply(value: String): RepoName = value

}

extension (repoName: RepoName)

def value: String = repoName

given ReadsRepo: Reads[RepoName] = (__ \ "name").read[String].map(RepoName.apply)

}

We basically used the same mechanism as we used for PublicRepos:

- defined

opaque type - created

applyconstructor for it - added

extensionmethod - defined

Reads

Splendid!

What about Contributor though? How would we want to represent each contributor? I guess it’s important to have at least:

username(text)contributions(number)

But, before modeling our contributor, it’s worth checking what GitHub API returns when we request for contributors.

For that, again, we can pick some organization and open source project owned by that organization and ping some endpoints.

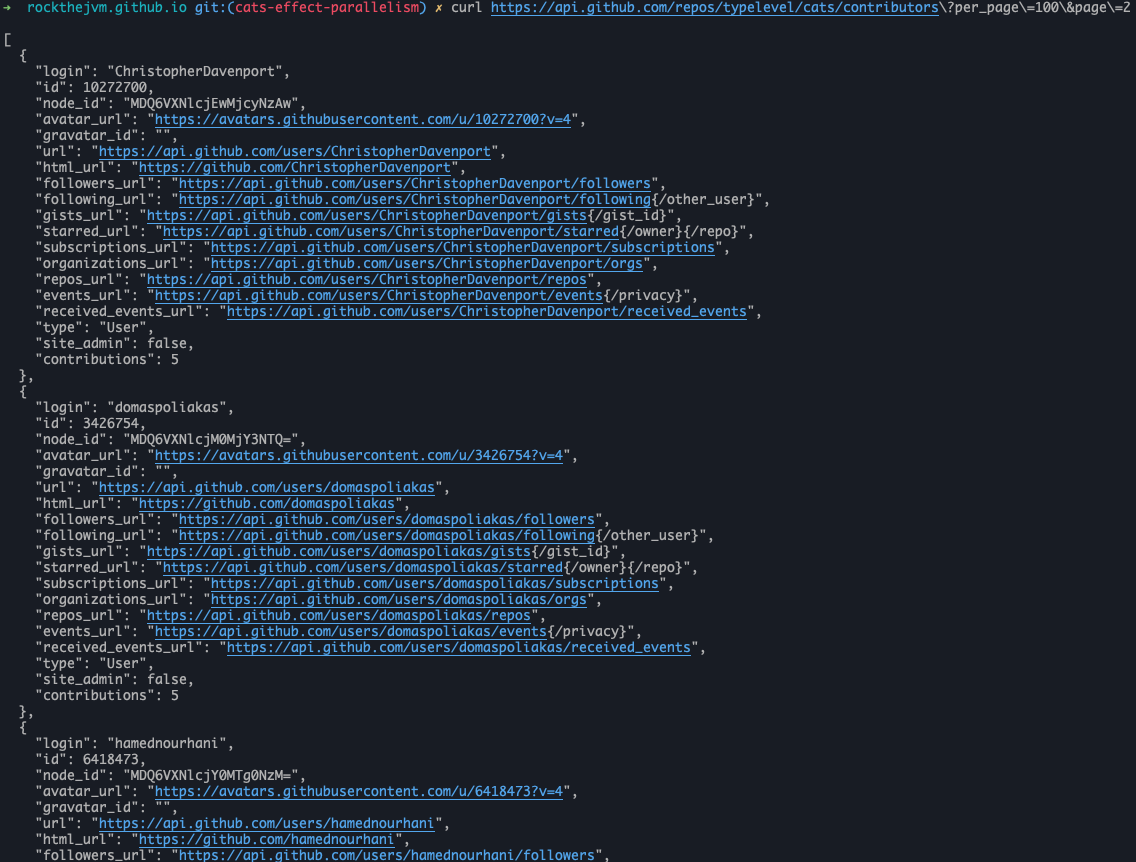

e.g, let’s pick typelevel ($orgName) and cats ($repoName).

Paginated API endpoint looks like: https://api.github.com/repos/$orgName/$repoName/contributors?per_page=100&page=$page

Notice, that the response is a JSON array. Important fields for us should be first and last of each - "login" and “contributions”:

So, our Contributor model could look like this:

object domain {

import play.api.libs.json.*

import play.api.libs.*

import Reads.{IntReads, StringReads}

import cats.syntax.all.*

/**

* old definitions

*/

final case class Contributor(login: String, contributions: Long)

given ReadsContributor: Reads[Contributor] = json =>

(

(json \ "login").asOpt[String],

(json \ "contributions").asOpt[Long],

).tupled.fold(JsError("parse failure, could not construct Contributor"))((lo, co) => JsSuccess(Contributor(lo, co)))

given WritesContributor: Writes[Contributor] = Json.writes[Contributor]

}

The case class definition needs no explanation, but… you may be thinking… why do we have Writes at all?

Good question! Writes[Contributor] is necessary because our HTTP server should also return this data to the client (more on that later).

This Reads[Contributor] can be a bit of tricky, so let’s explain what is going on there:

json => ...is an anonymous function taking a JSON value as input.(json \ "login").asOpt[String]extracts the value associated with the key"login"from the JSON object as an optionalString.(json \ "contributions").asOpt[Long]extracts the value associated with the key"contributions"as an optionalLong.(lo, co) => JsSuccess(Contributor(lo, co))is a function that takes the extracted values and constructs aContributorinstance..tupledextension method is coming fromimport cats.syntax.all.*and is used to convert the tuple(Option[String], Option[Long])into anOption[(String, Long)].foldmethod is used to handle the case where either of the options isNone. If any of them isNone, it returns aJsError("parse failure"); otherwise, it returns aJsSuccesswith the constructedContributorinstance.

We could have also used default values for each field and create an empty Contributor such as Contributor(login="", contributions=0), you’re free to choose.

Great!

Before we move on defining business logic, we should define one more domain object - Contributions. It may be a bit unclear why, let me explain.

We are building an HTTP server which is going to respond us JSON object, and you’re free to choose the format, however I’d go with something like this:

object domain {

import play.api.libs.json.*

import play.api.libs.*

import Reads.{IntReads, StringReads}

import cats.syntax.all.*

/**

* old definitions

*/

final case class Contributions(count: Long, contributors: Vector[Contributor])

given WritesContributions: Writes[Contributions] = Json.writes[Contributions]

}

This is where the previous definition of Writes[Contributor] becomes useful, it is internally (implicitly) used by Writes[Contributions].

In that case class definition the count will be just the amount of contributors for an organization whereas contributors will be a Vector of Contributor-s, sorted by Contributor#contributions field.

With that, we can finish the domain modeling and switch to the next part - building blocks for business logic.

7. Building blocks for business logic

Our goal is to make contributors aggregation fast. We’ve seen that there are more than a few API requests we need to make, some of them are paginated, some of them are not. Also, it’s important to define the order of execution and the general flow of the program.

After a few iterations and refinements I came up with something like this:

- send request to our HTTP server with organization name

- use organization name to find out how many public repos are available for organization name (let’s say 10)

- use this number (10) to issue N amount of parallel requests so that our server starts retrieving contributors for each project in parallel

- since there is no way to know how many contributors are available for a project we will need to send requests iteratively until they are exhausted, meaning that at some point the JSON response will contain less than 100 contributors, assuming that we expect to retrieve 100 contributors per page.

First of all, we will need to define a basic route which will let us accept organization name as a query parameter, so let’s add a new case for our routes definition:

def routes: HttpRoutes[IO] = {

HttpRoutes.of[IO] {

case GET -> Root => Ok("hi :)")

case GET -> Root / "org" / orgName => Ok(orgName)

}

}

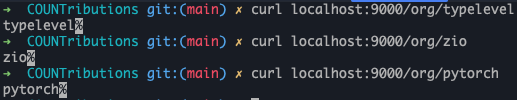

Let’s quickly test the new route and then proceed with the important stuff.

Great!

Here’s a list of things we need to prepare before writing the main logic:

- handling GitHub Token (configuration, loading, attaching to request headers)

- mechanism to create proper GitHub REST API URL-s (parameterization, pagination)

- general approach for issuing a single HTTP request (deserialization, error handling)

As soon as we have those components, we can start composing our main piece of logic.

Since this is a small project, it is not required to overwhelm ourselves with the approaches that quickly can turn into the rabbit hole of overengineering practices.

I suggest that we create a simple private methods in Main.scala which will be just called multiple times inside routes definition.

7.1 Handling Github Token

Github token is just a string which must be attached to request headers so that Github REST API rate limiter doesn’t prohibit us issuing huge amount of requests.

Let’s be simple and model that as a single field case class:

// other imports

import pureconfig.ConfigReader

import pureconfig.generic.derivation.default.*

// other imports

object Main extends IOApp.Simple {

final case class Token(token: String) derives ConfigReader {

override def toString: String = token

}

/**

* other code

*/

}

We’ve defined a case class named Token which derives from ConfigReader suggesting that it may be used in some configuration reading context.

The derives clause is part of the new Scala 3 feature called “derivation,” which allows automatic generation of type class instances for case classes and other data types. In this case, it generates a ConfigReader instance for our Token class, allowing us to read instances of Token from some configuration source.

In general, there are a few options for managing such things:

- configuration

- easy to set up

- env variable

- easy to set up

- key chains or secret management systems

- not so easy and requires some time to set up, definitely an overkill for a small project such as ours

- hardcoding

- very good for prototyping and development but extremely unsafe, as soon as you publish your token, GitHub will immediately expire it so that nobody can abuse it on your behalf

Since we’ve already seen ConfigReader and pureconfig dependency in our build.sbt it’s fairly easy to guess which option we’re using in this project, just a personal preference.

In terms of loading, it will just require one simple line of code in our run definition in:

object Main extends IOApp.Simple {

/**

* Token and logger definitions

*/

override val run: IO[Unit] =

(for {

_ <- info"starting server".toResource

token <- IO.delay(ConfigSource.default.loadOrThrow[Token]).toResource

// .. other code

} yield ()).useForever

Time to move on the next step.

7.2 Building GitHub REST API URL-s

There’s only a handful of URL-s we need to build for each organization:

- URL for loading the amount of public repositories (

PublicRepos) for some organization - URL for loading the names of public repositories (

Vector[RepoName]) for some organization - URL for loading paginated contributors (

Vector[Contributor]) forXrepository owned byYorganization

Let’s create such functions step by step in Main.scala:

def publicRepos(orgName: String) = s"https://api.github.com/orgs/$orgName"

It’s apparent that orgName will be injected in the base URL, giving us PublicRepos URL.

def repos(orgName: String, page: Int): String =

s"https://api.github.com/orgs/$orgName/repos?per_page=100&page=$page"

Here, orgName and page will be injected in respective places, giving us URL which upon requesting data returns the collection of repositories, from which we’ll read RepoName and turn that into Vector[RepoName] in the end.

def contributorsUrl(repoName: String, orgName: String, page: Int): String =

s"https://api.github.com/repos/$orgName/$repoName/contributors?per_page=100&page=$page"

repoName, orgName, page will be injected in placeholders, yielding us URL which returns the list of paginated contributors. After processing the responses, our app will turn this data into Vector[Contributor].

7.3 HTTP request fetch functionality

In order to implement a generic HTTP GET we will need to have a few other things in place.

Please keep in mind, that we’re working with http4s server and client, which means that eventually we’ll need to create things such as:

http4s.org.Request[IO]http4s.org.Uriorg.http4s.client.Client[IO]- …

Let’s define a function which will build Uri or IO[Uri] from the unsafe string.

import org.http4s.Uri

def uri(url: String): IO[Uri] = IO.fromEither(Uri.fromString(url))

Uri.fromString(url) gives us Either[IO, Uri] and with the help of IO#Either constructor - IO.fromEither we’re able to convert that into IO[Uri].

Before defining the HTTP GET we need one more thing - function which creates the Request[IO]:

import org.http4s.Header.Raw

import org.typelevel.ci.CIString

import org.http4s.{Method, Request, Uri}

def req(uri: Uri)(using token: Token) = Request[IO](Method.GET, uri)

.putHeaders(Raw(CIString("Authorization"), s"Bearer ${token.token}"))

Here’s the breakdown of the code:

def req(uri: Uri)(using token: Token)declares a function namedreqthat takes aUriand animplicit Tokenparameter.Request[IO](Method.GET, uri)creates an HTTP request with theGETmethod and the provided URI using thehttp4slibrary..putHeaders(...)adds headers to the request.Raw(CIString("Authorization"), s"Bearer ${token.token}")constructs the"Authorization"header with the value"Bearer ${token.token}".

So, in essence this function creates a request with an Authorization header, where the token is taken from the implicit Token parameter which we’ve defined earlier.

Sometimes, working with JSON can make our code a bit clumsy, so I suggest we add a nice syntax for de/serialization:

object syntax {

extension (self: String)

def into[A](using r: Reads[A]): A = Json.parse(self).as[A]

extension [A](self: A)

def toJson(using w: Writes[A]): String = Json.prettyPrint(w.writes(self))

}

This will enable easy conversion between our case classes and their JSON equivalents. As an example with a dummy case class:

case class Data(x: Int, y: Int)

given DataFormat: Format[Data] = Json.format[Data]

val data = Data(x = 1, y = 2)

val dataJsonString = data.toJson // "{"x":1,"y":2}"

val dataFromJsonString = dataJsonString.into[Data] // Data(x = 1, y = 2)

Now we can define a general HTTP GET functionality which will be used later multiple times:

def fetch[A: Reads](uri: Uri, client: Client[IO], default: => A)(using token: Token): IO[A] =

client

.expect[String](req(uri))

.map(_.into[A])

.onError {

case org.http4s.client.UnexpectedStatus(Status.Unauthorized, _, _) =>

error"GitHub token is either expired or absent, please check `token` key in src/main/resources/application.conf"

case other => error"other"

}

.handleErrorWith(_ => warn"returning default value: $default for $uri due to unexpected error" as default)

This function is designed for fetching data from an HTTP endpoint, parsing the response as JSON into a type A, logging failed IO computations and handling errors gracefully by providing a default value. The use of type classes like Reads indicates that are using type class-based decoding for type A.

Explanation:

client.expect[String](req(uri))sends an HTTP request using thereqfunction from our previous example and expects the response as aString(it is assumed that the response body is expected to be a JSON string)..map(_.into[A])transforms the JSON body into the concrete instance ofAusingReads[A].onError { ... }logs the errors ifIOfails.handleError(_ => ...)If an error occurs inIO, it logs warning and falls back to thedefaultvalue forA.

With that, we can move on to the most important part of our project - business logic.

8. Business logic

We have defined the domain and several building blocks for actually implementing the business logic, however, before writing the code we need to define the flow / plan and then execute it.

After a few revisions and refinement this is the plan I came up with:

- choose the organization (e.g

typelevel) - send HTTP request to our app on

host:port/org/typelevel - fetch public repositories information for

typelevelfrom a GitHub API endpoint - calculate the number of pages based on the number of public repositories (100 repositories per page) that is owned by

typelevel- this number will let us issue N amount of parallel requests in the next step

- use the computed number and fetch information about repositories to accumulate the list of repository names

- we will end up here with smth like

Vector("cats", "cats-effect", ... ,"fs2")

- we will end up here with smth like

- for each repository, start fetching contributors in parallel and accumulate their contributions sequentially

- So, if we have 3 repositories we will create 3 separate fibers and start accumulating paginated contributors sequentially until they are exhausted. It means that fiber A may take 500 millis, fiber B - 600 millis, fiber C - 300 millis. So, in total, we will have all results in 600 millis since it’s based on fork-join algorithm.

- Unfortunately there is no clear way of parallelising fetching the contributors for repository because we don’t know in advance how many contributors there are. However, if you feel brave you can play with different ideas and also try parallelising that, e.g you can use

fibonacciapproach and issue N amount of request on each iteration until they are exhausted, more on that later.

- group and sum contributions by contributor login

- create a

Vector[Contributor]instances sorted by contributions - generate a JSON response containing information about contributors and contributions

- send back the HTTP response with the JSON content

Let’s begin!

8.1 Accept organization name and define the # of parallel requests

object Main extends IOApp.Simple {

override val run: IO[Unit] =

(for {

_ <- info"starting server".toResource

token <- IO.delay(ConfigSource.default.loadOrThrow[Token]).toResource

client <- EmberClientBuilder.default[IO].build

_ <- EmberServerBuilder

.default[IO]

.withHost(host"localhost")

.withPort(port"9000")

.withHttpApp(routes(client, token).orNotFound)

.build

} yield ()).useForever

def routes(client: Client[IO], token: Token): HttpRoutes[IO] = {

given tk: Token = token

HttpRoutes.of[IO] {

case GET -> Root => Ok("hi :)")

case GET -> Root / "org" / orgName =>

for {

publicReposUri <- uri(publicRepos(orgName))

publicRepos <- fetch[PublicRepos](publicReposUri, client, PublicRepos.Empty)

pages = (1 to (publicRepos.value / 100) + 1).toVector // # of parallel requests that we can make later, e.g Vector(1, 2, 3) - 3 pages, so that we can have Vector of repository names

response <- Ok(s"# of public repos: $publicRepos, # of parallel requests: ${pages.size}")

} yield response

}

}

}

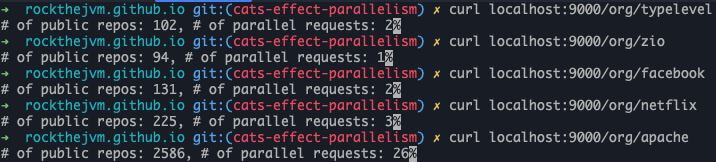

As you can see, we updated routes definition so that it finds out how many public repositories are available per organization.

The steps are:

- define a

publicReposUri - issue HTTP request to

publicReposUri - deserialize JSON response to

PublicReposwhich is an amount of public repositories - send response 200 OK with computed result

Below you can see how could we test this functionality:

8.2 Fetching all repository names

At this point we’ve already calculated the pages which holds the number of pages based on the number of public repositories (100 repositories per page) that is owned by some organization.

Since we have this value available, we can issue N amount of paginated requests and get back the Vector[RepoName], let me demonstrate this to you:

// other imports

import cats.syntax.all.*

import cats.instances.all.*

// other imports

object Main extends IOApp.Simple {

// other definitions

def routes(client: Client[IO], token: Token): HttpRoutes[IO] = {

given tk: Token = token

HttpRoutes.of[IO] {

case GET -> Root => Ok("hi :)")

case GET -> Root / "org" / orgName =>

for {

publicReposUri <- uri(publicRepos(orgName))

publicRepos <- fetch[PublicRepos](publicReposUri, client, PublicRepos.Empty)

pages = (1 to (publicRepos.value / 100) + 1).toVector

// let's calculate the vector of repository names

repositories <- pages.parUnorderedFlatTraverse { page =>

uri(repos(orgName, page)).flatMap(fetch[Vector[RepoName]](_, client, Vector.empty[RepoName]))

}

response <- Ok(repositories.toString)

} yield response

}

}

}

Let me explain how we calculated repositories step by step:

- The

parUnorderedFlatTraversefunction is used to perform parallel and unordered traversing of thepagesvector. For each page, it fetches the repositories using theuri(repos(orgName, page))to construct theURIandfetch[Vector[RepoName]](_, client, Vector.empty[RepoName])to fetch the repository names from the GitHub API. The result is aVector[Vector[RepoName]]representing repositories for each page. - The

parUnorderedFlatTraversecombines the vectors from different pages into a singleVector[RepoName]by flattening and concatenating them in a parallel and unordered manner. - The resulting

Vector[RepoName]is assigned to the repositories value. - Finally, the route responds with an HTTP Ok

Ok(repositories.toString)containing the string representation of the vector of repository names.

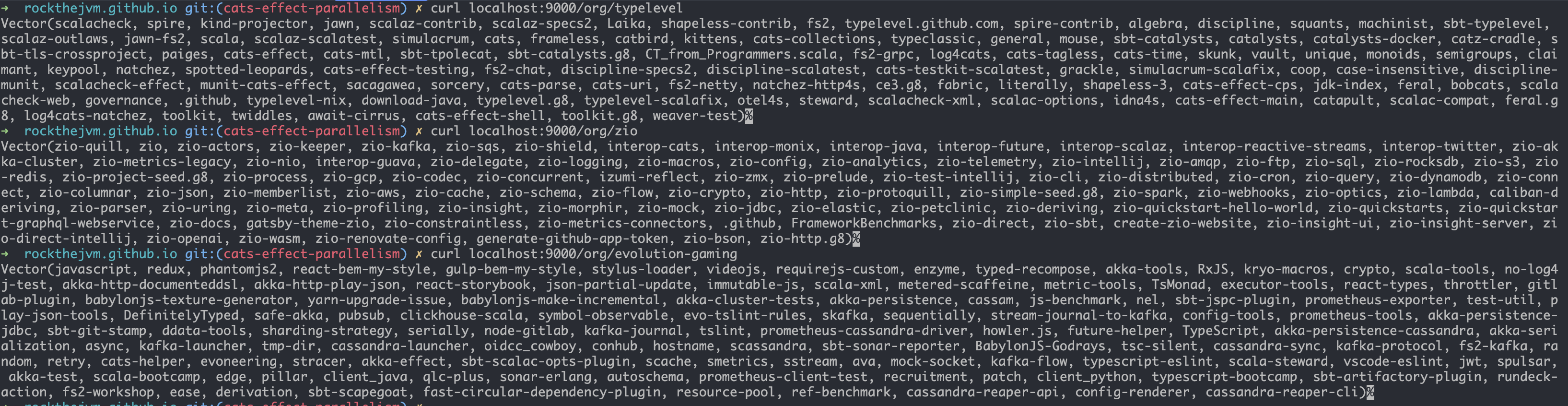

Let’s manually test the output for different organizations:

8.3 Start fetching contributors for each project in parallel and exhaust each iteratively

Since we have all the repositories, now we can start fetching the contributors of each project in parallel. We must notice that the results for this one are also paginated, however, we don’t know exactly how many contributors are out there for each project, it means that we’re limited in parallelism here and we have to iteratively fetch “next contributors list” until it returns the less than 100 results, indicating that it’s the last one.

With the business logic it’s equally important to define logging to indicate the progress and point out errors, if any.

// other imports

import cats.syntax.all.*

import cats.instances.all.*

// other imports

object Main extends IOApp.Simple {

// other definitions

private def getContributorsPerRepo(

client: Client[IO],

repoName: RepoName,

orgName: String,

contributors: Vector[Contributor] = Vector.empty[Contributor],

page: Int = 1,

isEmpty: Boolean = false,

)(using token: Token): IO[Vector[Contributor]] =

if ((page > 1 && contributors.size % 100 != 0) || isEmpty) IO.pure(contributors)

else {

uri(contributorsUrl(repoName.value, orgName, page))

.flatMap { contributorUri =>

for {

_ <- info"requesting page: $page of $repoName contributors"

newContributors <- fetch[Vector[Contributor]](contributorUri, client, Vector.empty)

_ <- info"fetched ${newContributors.size} contributors on page: $page for $repoName"

next <- getContributorsPerRepo(

client = client,

repoName = repoName,

orgName = orgName,

contributors = contributors ++ newContributors,

page = page + 1,

isEmpty = newContributors.isEmpty,

)

} yield next

}

}

def routes(client: Client[IO], token: Token): HttpRoutes[IO] = {

given tk: Token = token

HttpRoutes.of[IO] {

case GET -> Root => Ok("hi :)")

case GET -> Root / "org" / orgName =>

for {

start <- IO.realTime

_ <- info"accepted $orgName"

publicReposUri <- uri(publicRepos(orgName))

_ <- info"fetching the amount of available repositories for $orgName"

publicRepos <- fetch[PublicRepos](publicReposUri, client, PublicRepos.Empty)

_ <- info"amount of public repositories for $orgName: $publicRepos"

pages = (1 to (publicRepos.value / 100) + 1).toVector

repositories <- pages.parUnorderedFlatTraverse { page =>

uri(repos(orgName, page))

.flatMap(fetch[Vector[RepoName]](_, client, Vector.empty[RepoName]))

}

_ <- info"$publicRepos repositories were collected for $orgName"

_ <- info"starting to fetch contributors for each repository"

contributors <- repositories

.parUnorderedFlatTraverse { repoName =>

for {

_ <- info"fetching contributors for $repoName"

contributors <- getContributorsPerRepo(client, repoName, orgName)

_ <- info"fetched amount of contributors for $repoName: ${contributors.size}"

} yield contributors

}

.map {

_.groupMapReduce(_.login)(_.contributions)(_ + _).toVector

.map(Contributor(_, _))

.sortWith(_.contributions > _.contributions)

}

_ <- info"returning aggregated & sorted contributors for $orgName"

response <- Ok(Contributions(contributors.size, contributors).toJson)

end <- IO.realTime

_ <- info"aggregation took ${(end - start).toSeconds} seconds"

} yield response

}

}

}

getContributorsRepo is a recursive function which takes lots of parameters and continuously fetches paginated contributors for a certain repository unless it’s the last page.

Also, in the code snippet above, contributors and response are two important components of the HTTP route handling logic. Let’s break down their meanings:

contributors:

contributorsis a value that represents a collection of contributors to GitHub repositories belonging to a specific organization.- It is computed using parallel and unordered traversal (

parUnorderedFlatTraverse) over the repositories vector. - For each repository (

repoName), it fetches the contributors from the GitHub API in a paginated manner. - The

contributorsare accumulated into aVector[Contributor], and the final result is a collection of contributors from all repositories. - The contributors are grouped by their

loginnames andcontributionsusinggroupMapReduce. - The resulting grouped

contributorsare then transformed into aVector[Contributor]and sorted based on the contributions in descending order.

response:

responseis the final HTTP response that the route will return.- It is constructed using the

Okconstructor and contains the result of the entire computation. - The result is an instance of the

Contributionscase class, which wraps information about the total number of contributors and the sorted vector of contributors. -

The

contributorsare sorted based on their contributions in descending order. -The final result is serialized to JSON using the toJson method and included in the HTTP response body. - In summary,

"contributors"represents the processed and aggregated data about GitHub contributors, and"response"is the HTTP response containing this information in a serialized form. The route is designed to fetch information about public repositories, their contributors, and then provide a sorted list of contributors along with some summary statistics in the HTTP response.

Amazing! We should test it now, shan’t we?

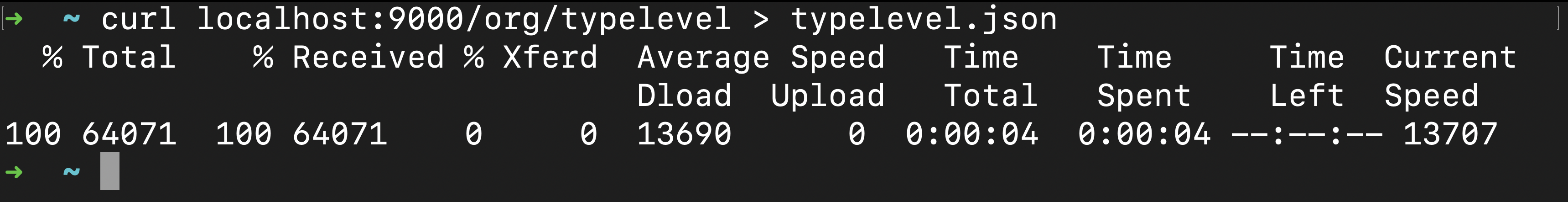

Assuming that server is running, we can just ping it with typelevel and save the JSON output in typelevel.json.

That way we can also see how many seconds it takes to do this operation:

You can see that it takes only 4 seconds to aggregate the contributors for typelevel - powered by functional parallel programming.

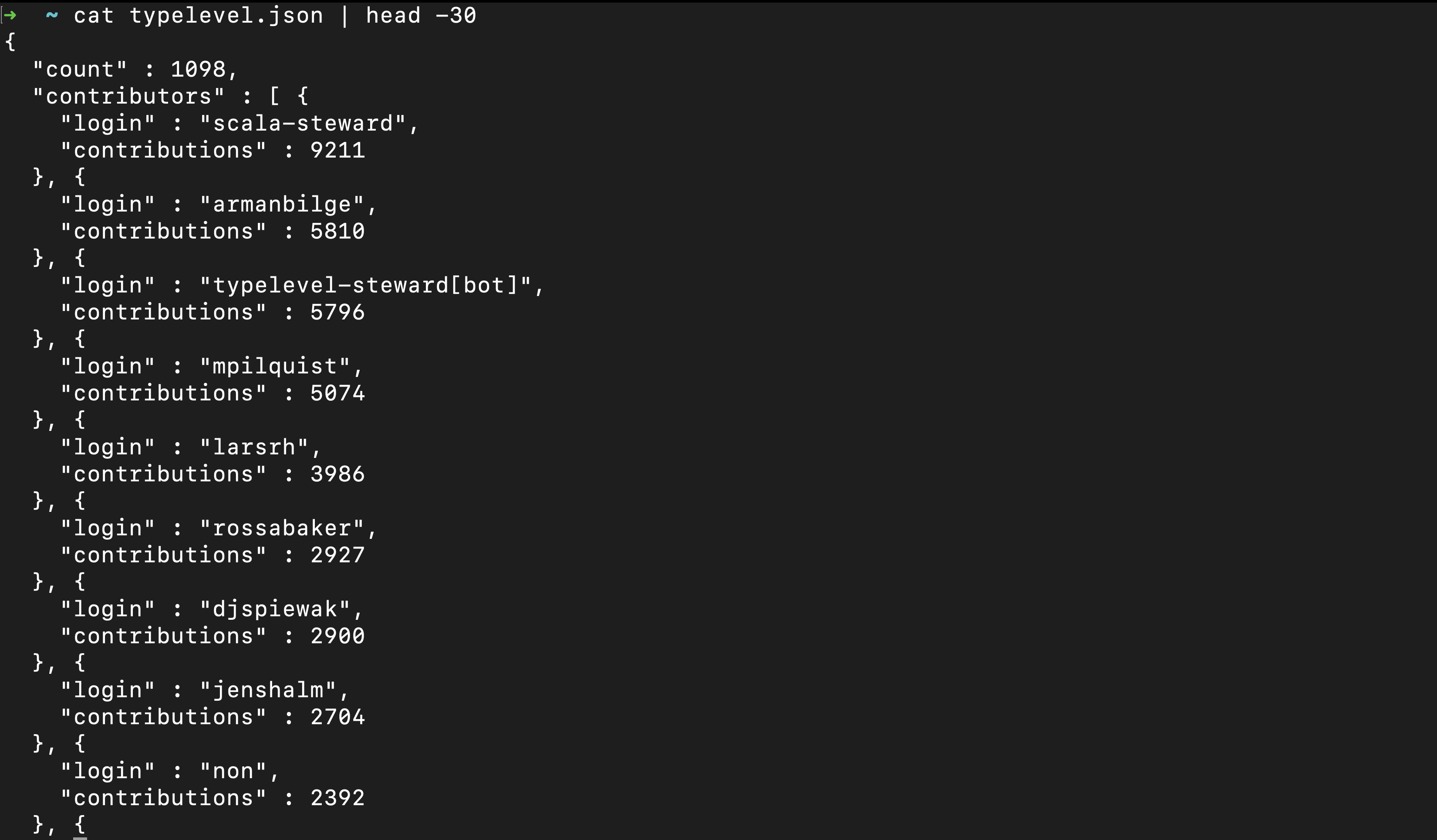

Let’s also have a quick look at the first 30 lines of typelevel.json:

9. Summary

We have built together the GitHub organization contributors aggregator. Here’s a summary of what we’ve accomplished, the tools and libraries used, and how we did it:

What We Built:

We built an HTTP server that accepts organization name and aggregates GitHub organization contributors in a matter of seconds. Our program is using minimal but sufficient domain modeling with play-json power do work with data. Additionally, it’s heavily backed up by the powerful extension method - parUnorderedFlatTraverse from cats which ensures that each HTTP request is performed in a separate fiber (hence, the power of cats.effect.IO).

Tools and Libraries Used:

Scala 3: the code is written in the Scala programming language.sbt: build tool which helped us tocompile,buildandrunour projectcats/cats-effect: we used the Cats Effect library for managing asynchronous and effectful operations using the IO monad.http4s: the http4s library is used for building HTTP clients and servers, handling HTTP requests and responses, and defining routes.pureconfig: used for loading application configuration from a configuration file.ember: used for building the HTTP client and server.play-json: awesome JSON library for Scalalog4cats: used for logging messages within the application.

How We Did It:

Exploration: We explored GitHub REST API a bit and planned the execution step by stepDomain modeling: We modeled domain objects with the help of Scala 3 opaque typesFunctional Programming: The code is designed using functional programming principles, leveraging the Cats Effect library for handling side effects and IO operations.Parallel Programming: We used the powerful extension method -parUnorderedFlatTraversewhich traverses the collection and runs an effect in a separate fiber for each object.Configurability: Application configuration is loaded from a configuration file usingPureConfig, allowing us to configure GitHub personal access token.

If you want to see the whole project you can view Source code

Thank you for your time and patience! Hope you learned something new today 😊